On the 1860 Tennessee census for Bradley county, James Harvey Norman is recorded as being 56 years of age, a farmer with a real estate value of $3,000 and a personal estate of $6,000. His wife Nancy was listed as 60 years old. A son, Cyrus Norman, was living in the household. There were six slaves listed on the farm in the 1860 slave census: a 26 year old female and five children, three of which were mulatto. These young children were apparently born while under the ownership of this Norman family.[1]

James Harvey Norman was born January 29, 1804 in Virginia and at an early age was brought to Tennessee. Circumstantial evidence points to James as being the son of Courtney Norman and Alice Jett, but nothing has been proven.

James married Nancy Wiley in Roane county, Tennessee on February 26, 1829. [1a]

Cyrus Alexander Norman was born to James and Nancy on December 28, 1829 in Knoxville, Knox county, Tennessee. Another son, William Jett Norman, was born in 1831.

By the year 1850 they lived near the small town of Cleveland in Bradley county, Tennessee which is located in the "Great Valley" on the southeast corner of the state. The county was formed in 1836 from lands previously taken from the Cherokee and sold to settlers.

James bought a farm in 1852, just a few miles north of this town. Today, Norman Chapel Road is located in North Cleveland in the vicinity of the old Norman farm.

James was probably not a wealthy man, but it appears he was educated and quite capable of supporting a family in a fairly comfortable manner. The 1862 Bradley tax assessment list shows him owning 160 acres. His son Cyrus had 47 acres.

Neighbors of the Normans included the Cobb, Cowan, Sprigg and Clingan families, who all lived close together about a mile or two northwest of town along a ridge called Candies Creek Ridge.[1d] Theses families would all eventually be related by marriages.

Jame's son, Cyrus, married the neighbor's daughter, Martha Jane Clingan, on February 17, 1862. She moved to the Norman farm to live with Cyrus and his parents.[2] The newlyweds had no idea that the War between the States, which was beginning to mount, would have such an impact on their lives.

The Civil War

On May of 1863, Cyrus, who was living under the certainty of being conscripted into the confederate army, escaped with a group of conscripts north to Kentucky. He then turned and re-entered Tennessee, going to Nashville which was under Union control, where he found work under the Union Army on the river docks.

Isabel Cobb; the daughter of Joe Ben Cobb and Evaline [Clingan] Cobb, wrote memoirs of her childhood in Bradley County.

She said that her uncle William Cowan and her father?Joe Benson Cobb, crossed to the Union side to serve in the commissary at Nashville during the Civil War in order to avoid bloodshed of which they detested.

Before departing, William B. Cowan had been visited by an unhappy rebel who had pulled a weapon on Mrs. Cowan and demanded to know where William was hiding. William was in the cellar, and probably decided then it was time to leave while he could.[2a]

From Nashville, on June 6, 1863, Isabel's father, Joe Benson Cobb, wrote a letter to his brother-in-law, Captain Judge K. Clingan of the Union Army, informing the Captain of the death of his brother, James Clingan, who had died of typhoid fever. He wrote his sympathy and explained that he and their brother-in-law, Cyrus Norman, had bought the deceased James Clingan a new set of clothes and had buried him in a metal casket. Cyrus himself wrote a letter on the back of Joe's. He wrote, Dear Brother, I am in this place stopping with Brother Joe. He was writing to you and asked me to drop a few lines to you which affords me the greatest of pleasure to inform you that I am in common health, under the protection of the greatest and best government the sun ever shone upon. As it is late at night I shall not weary you with a long letter. Suffice to say that 82 conscripts arrived at Summerset, Kentucky, safe and sound on the 23rd of last month (last May). I left home on the 14th May. All of our connections was well at the time and the health of the country is generally good. I had intended going up to Carthage to see you but I learn it is considered dangerous so I have concluded to remain here for a few weeks.

Judge, Oh how I would like to see and talk for one hour with you for it seems to me that you have been gone ten years but I hope and trust it will not be a great while before our downtrodden families will be liberated from the oppression of rebellion and holsome laws established again. So I shall close by asking you to accept my best wishes for your success. Give my respects to the boys and I will remain, Your brother, C.A.Norman.

According to local history, the men's hometown of Cleveland, Tennessee suffered severely during the Civil War and the country for miles around was laid waste by troops from Sherman's invading army (court records were burnt in 1864, whether by accident or retribution by Southern sympathizing citizen's was never known).

At the onset of the war, Union loyalists had raised a Union flag over the town but it was quickly taken down when the county came under Confederate control.

Union Loyalists started holding secret meetings at the county clerk office of Joseph H. Davis to consult and devise ways of assisting those in their efforts to escape north and in planning for their own safety. Among those were John McPherson, A.A. Clingan, Capt. James H. Norman, William Cate, G.B. Thompson, Ike Henry, George T. Packer, A.J. Cate, Felix Hirkeart, John C. Gant, Jesse H. Gant, S.P. Gant, Levi Tuwhill, William Hunt, Samuel Hunt, Dr. John G. Brown, J.S. Robertson, Dr. Armstrong Menalb and many more according to Joseph H. Davis.[3]

Although these meeting were held in secrecy, word eventually made its way to the local Confederate leader who threatened to "fire upon the office."

It became a danger for these Union men to appear in town.

While Cyrus Norman and many others escaped to the Federal lines at Nashville to avoid being conscripted or put in a prison camp, his father, Captain James H. Norman, was busy in the "underground railroad" helping conscripts and deserters move through the mountain ridge to the Federal lines. These men frequently hid in caves in the ridge. Some with no shoes or shirts, others starving and lost, they would show up at the Normans, Clingans and other farms all along the ridge. These welcoming farms were known through the "Grape Vine Telegraph" which was the secret communicate spread by Union supporters in Confederate controlled regions.

William Cate's farm was near the ridge and adjoined that of the Normans. William Cate was a prominent farmer and known 'Lincolnite' (Northern sympathizer) who exchanged Confederate for Northern money and helped finance furnishings for these hiding men when approached by Captain James Norman for help. Cate also distributed mail through the community that James brought from the Union side and supplied James with news from town and the Confederate camp just south of town.

Cate was also said to have threshed and stored away Captain Joe Ben Cobb's wheat for Cobb while he was away from his family serving the Union.[3d]

In 1864, the area came back under permanent Union control. The race to the North by those fearing conscription stopped, and it was the Confederate sympathizers turn to lay low and who were often forced to flee south to escape the retaliation of their Northern-sympathizing neighbors.

When it became apparent that the county was no longer threatened of being overtaken by Confederate troops, government began the process of reorganizing and returning to official business. James H. Norman was the County Trustee through 1860-1864;[3A] although very little could have been done in that time period because of the turmoil in the county.

James, while apparently still serving as the trustee, died February 17, 1865 shortly before the end of the war. He had lived long enough to realize whom the ultimate victor would be in the brutal civil war. [3B]

James was buried in the City Cemetery in Cleveland. (20 years later, the City Cemetery's graves were all moved to the Fort Hill cemetery; a cemetery given its name for the Union bunkers that were built into its hillside during the later stages of the war.)[3C]

James title of "Captain" could have come from the county militia duty that Bradley county had maintained until 1858, since no official records can be found of his service in the regular forces. County militia had been important as a deterrent to "black-uprisings" until the issue of freeing slaves became a subject of much argument.

Jame's son, Cyrus, had returned to the farm before James died, but like all Union men, he had been forced to hide much of the time in the woods until the county was clear of Confederate forces.

When the local Union men returned at the end of the war, supporters of the Sixth District of Bradley county just north of Cleveland, put William Cate in charge of purchasing provisions for a barbecue at the farm of Colonel Stephen Baird to honor the return of Bradley County Union soldiers.

William Cate wrote, "Some of these Union supporters who gave were very poor and could hardly get bread for families at the time."

A petition for this event was drawn and read;

"Cleveland, Sept. 25, 1865"

We the undersigned citzens of the 6th district [just north of Cleveland during Civil War] do agree to pay the several amounts added to our names to be appropriated in provisions to make a barbecue for the returned Union soldiers.

J. Pierce- $1, S. Hunt-$1, J. Robertson-$2, A.E. Blount-.50, C. Pierce-.50, J.H.Gant-$5, P.M. Graigmiles-$5, A. Grant Culard-$1, William Cate-$10, J.C. Gant-$5, G.B Thompson, -$2, D.B. Oneal-$1, J.C. Tipton-$1, H Craigmiles Culard-.50, L.L. Orment-.50, ? Orment-.50, William Low-$1, and J.H. Norman-$1.

Apparently a few of these were freed slaves; and one of the signees [Craigmiles] was a known pre-war slave dealer.

James Norman had died prior to this barbecue; so someone, perhaps Cyrus, contributed in honor of his memory.

In 1872, James Norman's neighbor, William Cate, filed claims against the Union for damages to his farm property suffered during the Civil War.[3D] In order to show Union loyalty, he claimed among other things, to have supplied Captain James H. Norman with money to move conscripts over the mountains to Federal lines in Nashville.

Justus Campbell Steed, age 54, under oath, disputed Cates claim of being a Union supporter. Justus was the nephew of James H. Norman, whom he described as a man of property.

Justus said, "He was my Uncle and died about the close of the war. He had a good farm, six or seven negroes and had fine stock worth as much as any man in the county. He was known throughout the county as one of the best [livers] and best farmers in the county. He alway had money and had never been without since a young man."

He claimed James hadn't trusted Cate.

He also said, "James Norman was about sixty when he died near the end of the war. I borrowed money from his widow in a month or two after he died."

There is reason to believe Steed was perhaps a little boastful, if not outright lying. He had an ongoing personal feud with Cate.

Another witness, John.F. Larrison, age 66, said he lived four miles north of Cleveland and stated he was Jame's first cousin.[4] Larrison said he knew James well. He described him as an industrious, money-making man, as having a good farm and plenty of fine stock and never without money.

John stated, "I have frequently borrowed money from him and know of others doing the same. James was not in the habit of borrowing money but he kept it to lend."

James H. Brown, age 66, said he had known Captain Norman to bring letters from the union lines and give them to Cate for distribution.

Brown said, "Norman came to my house once while Cate was there. I got a torch light and Norman sorted out a package or two of lettters or papers of some kind that he said had come through the federal lines. He gave them to Cate for distribution; also some confederate money to be exchanged. I knew that "Captain" Norman had been through the federal lines and that Norman often came privately to Cate's house to get the news from Cleveland."

Brown stated, "Norman told me that he didn't let [anybody] but myself, Cate and one or two others know what he was doing."

Joseph R. Taylor, age 42, was a farmer and brickmason near Cleveland. According to Joseph, James H. Norman had been the quardian of Joseph and his brother and sister. Joseph stated that James was poor and not in a condition to lend money, but was known to borrow it. He didn't think the Norman property had ever been worth more than $2500, and offered proof of this by saying that part of the property had consisted of only a negro woman and small children.

He did say though, "James was always considered an upright, honest man."

He spoke well of Norman in spite of the fact that Joseph was a Rebel and the Provost Marshall for the area during the first year of the war and whose responsibility it was to keep Union activity quelled.

Joseph had left that position in Bradley in 1862; joing the regular rebel army where he was eventually promoted to second lieutenant before being captured at Vicksburg and sent to Camp Chase, Ohio.

As a prisoner of war there, he had written home to his wife telling her that he had "a nice breakfast of slick-tailed squirrels and sold some he did not want for five cents each." When the war ended, Joseph walked the 500 miles back to Cleveland, Tennessee. [4a]

In conclusion on William Cate's claim against the Union; Cate said that he had no personal claim against James Norman, but instead described him as "a staunch Union man and a gentleman besides."

William Cate stated that, "Norman purchased a farm adjoining me in 1852 for which he paid six hundred dollars on a long credit and was pressed very hard to pay for it and never added any more land to it."

He said, "When he died his estate was worth about twelve hundred dollars after his debts were paid and I don't consider that this has any to do with my claim. I just wish to show that Steed and Larrison had lied."

Cate successfully received compensation for his losses to the Union.

Cyrus and Martha Norman were still on the Norman farm near Cleveland after the war.[4B] Included in the household were children: James Alexander, Mary Jett, Albert Clingan, Cyrus William and William Blythe. Cyrus's widowed mother Nancy was still living with them.

Cyrus had been a member of the Masons as early as 1855.[4c] Meetings were halted during the war and didn't resume until May 1865; at which time Cyrus was elected treasurer of Lodge 134 in Cleveland. The Mason lodge was actively involved in promoting education and Cyrus was one of many local residents who signed a petition around May of 1865 asking for the state to finance a female college in the rebuilding county.

In April of 1867, Cyrus paid his brother, William Jett Norman, $1,200 for William's share of their father's estate. William was living in Chambers county, Texas.

John Larrison said in his interview for William Cate's claim, "His (James Norman's) son moved to Texas many years earlier and returned about 1873 to take his mother out." He also said she died before May 1875."

Apparently William J. Norman had taken his mother Nancy to Texas, but her place of burial is not known.

Although it appears Cyrus may have initally planned to continue living in the region after the war, the family would uproot, journeying west in what was surely a quest at bettering their war-torn lives.

the Cherokee Connection

Cyrus Norman's wife, Martha Jane, was the daughter of Alexander Adam Clingan and Martha [Blythe] Clingan and was part Cherokee from her mother's side.

Cyrus's mother-in-law, Martha Blythe, according to Clingan family history and Indian records, was a granddaughter of Richard Fields, who was a Cherokee leader assassinated by his own people for making an unauthorized alliance with the whites. (This was the Fredonian Rebellion of 1827 in Texas.[4d]) Richard Fields has been thought to be a descendent from the lineage of Elizabeth Coody, a full-blood Cherokee of the 'Long Hair Clan' (unverified). Elizabeth Coody was married to Ludovic Grant; a Scottish trader with the Cherokee in the 1730's.

Cyrus's father-in-law, Alexander Adam Clingon, served as the first sheriff of Bradley county from 1837 to 1838. His name appears in early court documents for Bradley County, including a few where he himself was the defendant.

"Alex" died at his home in 1864 after journeying through the Union lines to visit his son, Captain Judge K. Clingan, at Knoxville, where he contracted smallpox.

Alexander's wife, Martha [Blythe], died in 1868 from a spider bite and blood poisoning.[4e]

Their daughter Martha, who was Cyrus's wife, had 15 brothers and sisters. One brother, William David Clingan, settled to ranch a mile east of Gibson Station, which is just a few miles south of present day Wagoner. He, along with a couple of the Cobb brothers who were trading with the Indians at Webbers Falls, were writing the folks back home in Tennessee of the great opportunities waiting in Indian Territory for those who cared to come.

At this time, anyone with Cherokee blood or married to a Cherokee could use all the land they needed in the Cherokee nation as long as it interfered with no other individual.

So starting in the early 1870's, members of the Clingan, Cobb, Cowan, Spriggs and Norman families made their move to the Cooweescoowee District of the Cherokee Indian Territory. (This would be the area just east of Wagoner and Gibson Station.) Cyrus Norman's family started their journey in the Fall of 1872 and moved by wagon. They settled and commenced farming and raising stock about six miles east of present day Wagoner.

The children of Cyrus Norman grew up in Cherokee Indian Territory attending Riverside school near Grand River. [5]). The school was located a few miles southeast of what eventually became the town of Wagoner. By May 1876, the school had a total of twenty-four students including the five Normans, two Cowans and seven Cobbs, ranging in ages from four to nineteen.

A few years later, two of the Riverside students, William Cobb and Alex Cowan, were involved in a gunfight on the range near William Clingan's farm at Gibson Station. They were approached by a group of Creek Negroes who were angry about the lynching of two of their compadres. Bill (William D.) Clingan and William Cobb had been identified as being involved in the lynching of two presumed cattle rustlers near Tallahassee and the Creek Negroes were searching for revenge.

The young William Cobb was fatally wounded when he pulled his gun from his holster. Alex Cowan was seriously injured but able to stand his ground until the attackers fled the area.

Two of the attackers were later sentenced to hang by Judge G.W.Parks, who was himself a relative of the young Cobb.[6] This may explain why at least one of the attackers was later reprieved by the Principal Chief. Bill Clingan was ordered to give himself up to the authorities for possible involvement in the hangings, but charges were dropped for lack of evidence.[6a]

Cyrus's Children

Cyrus Norman and Mr. [Joe Ben?] Cobb visited the Cherokee Male Seminary south of Tahlequah in late 1883; checking it out as a possible place of education for their children.

Cyrus's son, William Blythe, died while attending this school on April 4, 1885. He was 16. [2]

Cyrus's daughter, Mary Jett, was often on the Cherokee Female Seminary honor rolls, and graduated there on May 13, 1886.[7] She married a fellow graduate, Dr. George Albert McBride, on Feb. 17, 1887. Dr. G.A. McBride became the Medical Superintendent for the "Cherokee Orphan Asylum" in 1893 and then president of the Indian Territory Medical Association in 1899. They settled to live in Fort Gibson.

Mary Jett's father, Cyrus Alexander Norman, died of "striangulated hernia" according to the obit in Tahlequah's "Cherokee Telephone". His funeral took place on the 15th, March 1891 at 10 o'clock at the family house, Rev. R.C. Parks, officiating. The interment was made at Riverside Cemetary. He was 61.

His son, James Albert Norman, described his father in writing as a "progressive citizen, a typical representative of the "Square Deal" of all things; for the democratic idea of economics and social security; for the greatest good to everyone. He was a man of the highest character and integrity, thereby helping to make the Nation and world a better place than when he came."

He also wrote, "Cyrus was a member of the Masonic Order and of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church for many years and practiced his professions. He was esteemed as a loving and faithful neighbor". [2 ]

From this description it was apparent that Cyrus was well-loved by James and the rest of this family.

In 1893, a United States Congressional act forced on the Cherokee Nation in part for the Cherokees siding with the Confederacy, called for the division of the Cherokee Nation lands into allotments to be given to all its tribal members. This was the U.S. government's way of enabling the ever encroaching white settlers an opportunity to buy land from individual Indians instead of having to deal with an unwilling Indian nation.

Each Cherokee member enrolled by 1906 received 110 acres or the equivalent of; some property was judged worth more, such as that located in the developing Wagoner township. Children received land also, though not quite as much. The total allotment given to families would be bits and parcels scattered about, often too far spread to be of any use, with the result being much of it sold to white settlers.

Martha Norman, who was already enrolled, had her children added before the 1906 deadline.

On the 1900 census, she lived in Wagoner on Church street. Included in the household were her son Albert C. Norman and his wife Josie.

On the 1911 census, Martha had moved to live with the McBrides in the Fort Gibson area. She died there on June 3, 1914. She left an estate of $1218.[9] Her death certificate was signed by her son-in-law Dr. McBride. She was 77 years old and had died of impaction of the bowels according to Dr. McBride.

Within a year of Martha dying, the McBrides moved to Harlingen, which is situated at the southern tip of Texas, where they lived the rest of their lives.

Jame A. Norman described his mother, Martha, as "a wonderful woman and a wise and loving mother. She was a great believer in the Golden Rule and thus a good and loving neighbor, beloved by all who knew her."

He said she was an Eastern Star member and a loyal communicant of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church for many years.

She was buried with her husband, Cyrus, at Rock Creek cemetery, located about four miles east and one mile south of Wagoner. Their bodies were later exhumed and moved just southeast of Wagoner to the Pioneer cemetery because of the creation of the Fort Gibson lake. (note: Of 235-250 graves in the removed cemetery, only 85 to 90 could be positively identified.) [8B]

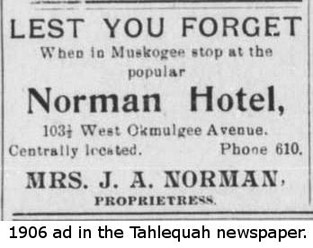

Cyrus's son, James Alexander, can be found in some of Oklahoma's history books. James was a farmer on the Arkansas river bottom and owner of the Norman Hotel in Muskogee. An article in "Chronicles of Oklahoma" mentions that he owned a hotel in Muskogee and there is a Norman Hotel at 103 1/2 West Okmulgee in early Muskogee phonebooks. James was looked upon as "something of a promoter" of the Muskogee area. When the people of Oklahoma territory began clamoring for statehood, the Indian nations began protesting. So, James, who was only 1/16 Cherokee and without any authorization from any tribe, called for a convention to be held in Muskogee to form a separate state of the five civilized tribes, which he suggested be called Sequoyah. Others took up the cause, and James helped author the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention of 1905. He ran in several elections hoping to represent one of twenty-six Indian territory districts at the convention. Although he failed to gain any of the posts, he was chosen to serve as one of only a handful of permanent officers to the Convention.

Muskogee. An article in "Chronicles of Oklahoma" mentions that he owned a hotel in Muskogee and there is a Norman Hotel at 103 1/2 West Okmulgee in early Muskogee phonebooks. James was looked upon as "something of a promoter" of the Muskogee area. When the people of Oklahoma territory began clamoring for statehood, the Indian nations began protesting. So, James, who was only 1/16 Cherokee and without any authorization from any tribe, called for a convention to be held in Muskogee to form a separate state of the five civilized tribes, which he suggested be called Sequoyah. Others took up the cause, and James helped author the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention of 1905. He ran in several elections hoping to represent one of twenty-six Indian territory districts at the convention. Although he failed to gain any of the posts, he was chosen to serve as one of only a handful of permanent officers to the Convention.

The Sequoyah Convention caused an uproar in the state. It was watched carefully across the nation by government leaders, because this was the first convention calling for statehood which had not been authorized by the U.S. Congress. Although the convention failed to produce the desired separate Indian state (it was turned down by Congress), it did induce the Five Civilized Tribes to consent to joint statehood and greatly influenced the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention where the two halves of Oklahoma were joined in statehood on November 16, 1907.

It seemed to be James greatest moment. He apparently was involved in more government work and lived in Oklahoma City for a while. He died at that city, but was buried at Wagoner.

Cyrus's son, Cyrus William (Wiley), is known to have owned or operated a store in downtown Wagoner. In 1911, he had a little run in with the law, regarding the distribution of alcohol from the downtown City Drug store. He was rumored to be a heavy gambler and to have lost quite a bit of money. He died in 1941.

Another of Cyrus's sons, Albert, attended business school at Sedalia, Missouri for a while but returned to farming. He met a girl from Texas, Josephine Hood,, who was visiting family in Oklahoma. They married in Waco, Texas on March 22, 1900, apparently against her family's wish. She was disowned by her family.

A tall, big-boned lady of pleasing appearances, she was born in Mart, Texas to Georgia-bred parents, James Hood and Eliza Morgan, and was supposedly 1/16 Indian but never enrolled. (Cherokee, I've been told.)

Albert was a stern, devout Presbyterian who came to disagree vehemently on religious beliefs with his wife Josie, who was the third charter member of the Wagoner Pentecostal Holiness Church. They managed to raise a family which included Mary Jett, Albert Clingan Jr. (Burt), Louis Edward, Howard Owen, Clara Iola, Erman Blunt, Lora Josephine, Wiley William, Rheuben Allen, Raymond Oliver, and Virginia Oklahoma, who died of pneumonia when she was four and Bessie Louetta, who died of blood poisoning at 6 months of age. [10]

Albert and Josephine separated twice. In fact, it's likely they may have divorced and had it annulled later. She is listed as 64 years of age and "divorced" on the 1940 census. Albert was living with his son Louis and was listed as "Widowed". The old records of Judge Charles Watts are in the University of Oklahoma Western History Collection and the case of

A.C. Norman versus Josephine Norman is included there. He also settled the matter of A.C. Norman's estate just a few years later.

The Normans at that time had a running feud with the neighboring Williams family. One particular account is that of Albert's son, Rheuben. Rheuben shot a wolfhound belonging to the Williams because it was eating chicken eggs. In return, the Williams killed a Norman calf, cut its ears off, and left it to rot. Eventually this feud burned out and a Norman even married the despised Williams family. Unfortunately, this union led to an eventual divorce. (This writer's parents)

Four of Albert's children: Rheuben, Louis, Wiley and Howard went on to become preachers of the gospel.

In his later years, Albert Norman developed cataracts and became blind. He died of heart failure in 1945 in Kansas City, where he lived in the home of his son Louis. His 102 acres of land was divided with his widowed wife receiving five-fifteenths and his children each receiving a fifteenth.[11] His widow Josephine died only two years later at her daughter Clara's home at 3114 Woodland Avenue in Kansas City. [12]

Albert and Josephine were both buried in Wagoner at the Elmwood Cemetery.

Photo of Wiley, Albert, Mary Jett, and James?Cyrus's offspring.

VIEW CREDITS AND SOURCES FOR NORMAN HISTORY

CYRUS NORMAN'S WAR COMPENSATION CLAIM